Intense mining and the Second World War have left clear traces throughout the Ruhr region, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. However, today these are no longer visible in most cases – they are hidden underground. This poses a great danger for construction sites and should be investigated before any work begins.

Reports of the discovery of unexploded ordnance and sinkholes are commonplace between the German Rhine and Ruhr rivers, and the effects of large-scale subsidence are barely recognizable at first sight. For example, Essen’s city centre areas are about 30 metres deeper today than before intensive coal mining began.

In more than 700 years of mining, there were about 1,300 mines in the Ruhr area. There were around 280 in both Bochum and Essen alone, plus about 250 in Sprockhövel and about 120 in Dortmund. Until the introduction of the Prussian mining law in 1865, mine owners were not obliged to map their mining operations and submit them to the region’s mining authority. Therefore, all mining activities before that time are poorly documented or, in some cases, not documented at all. In the post-war period, illegal mining also took place in some areas, leaving more undocumented unfilled cavities. The total number of openings and tunnels in the southern Ruhr region alone is estimated at around 60,000, of which only about 27,000 have been recorded or discovered to date, and only a fraction of these have been backfilled and secured. The problem zones with acute dangers due to sinkholes are located specifically where mining was only carried out to a depth of 100 metres.

As if this were not enough, the bombing by the Allies during the Second World War also left thousands of unexploded bombs underground, which remain undiscovered. According to a report by the press office of the North Rhine-Westphalia state government, 1.3 million tons of explosives were dropped on the territory of the Deutsche Reich during the Second World War. About half of air raids were concentrated in North Rhine-Westphalia state, and a high percentage of these were focused on the cities with their infrastructure and industrial facilities between the Rhine and Ruhr rivers.

Experts assume that about 15 per cent of the bombs were unexploded. Therefore, up to 100,000 tons are still undiscovered, hidden in the ground throughout Germany at a maximum depth of eight metres, depending on the weight, size and subsoil. In North Rhine-Westphalia alone, between 2,000 and 2,500 bombs are discovered and cleared each year. In Essen, which was particularly hard hit, it is assumed that of the 14,000 unexploded ordnance suspected there, only a half could be found and defused during the war and reconstruction. This means thousands more lay hidden underground – not counting grenades, hand grenades and mines. All of the unexploded ordnance, as well as the near-surface mining, pose very special dangers. In the affected areas, special precautions must be taken even before the start of construction work. The owner is responsible for ensuring that a construction site is free of explosive ordnance, and the legal successors of the mining companies – if known or still in existence – are responsible for locating and removing old mining contamination. If no legal successor can be identified, the state of North Rhine-Westphalia takes over.

Investigating the soil to find old explosive material

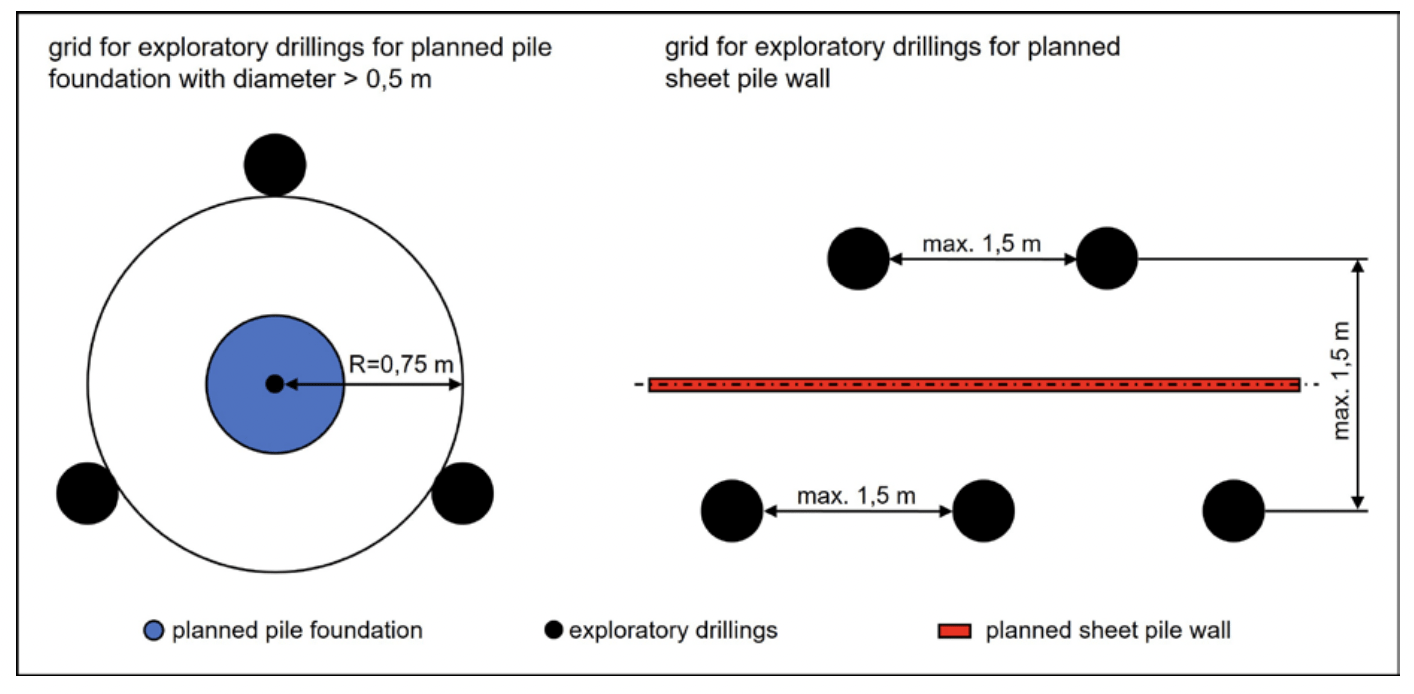

When evaluations of old documents or aerial photographs reveal suspected explosive ordnance, the first step is usually to probe from the surface using ground penetrating radar, geomagnetic or electromagnetic systems. Depending on the soil conditions, these methods only provide reliable results down to a depth of three metres, or in exceptional cases, up to five metres. If no hits are found here, depth probing can be started. A classic method for locating unexploded bombs at depths of up to 15 metres is geomagnetic depth probing, in which ferromagnetic bodies (iron) are detected at an average radial distance of 0.75 metres from a borehole.

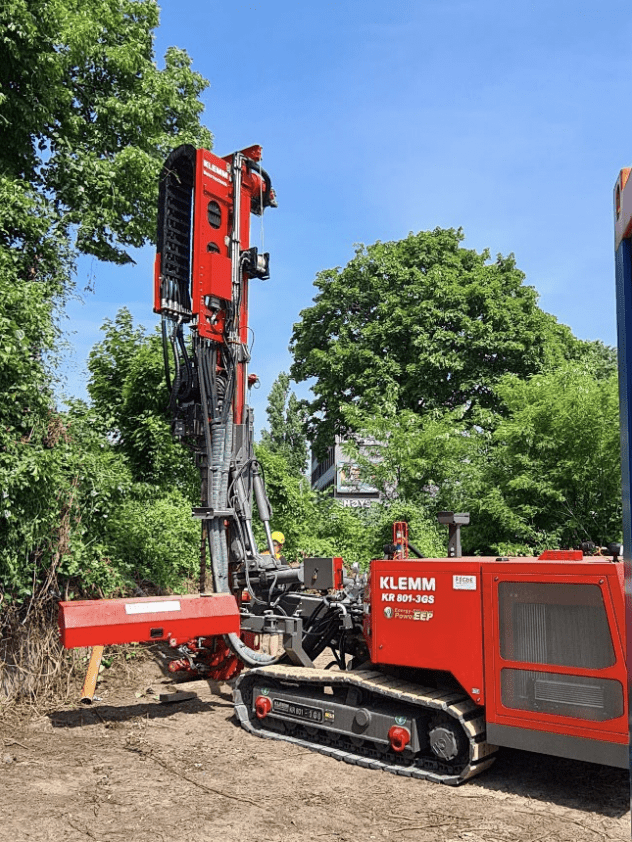

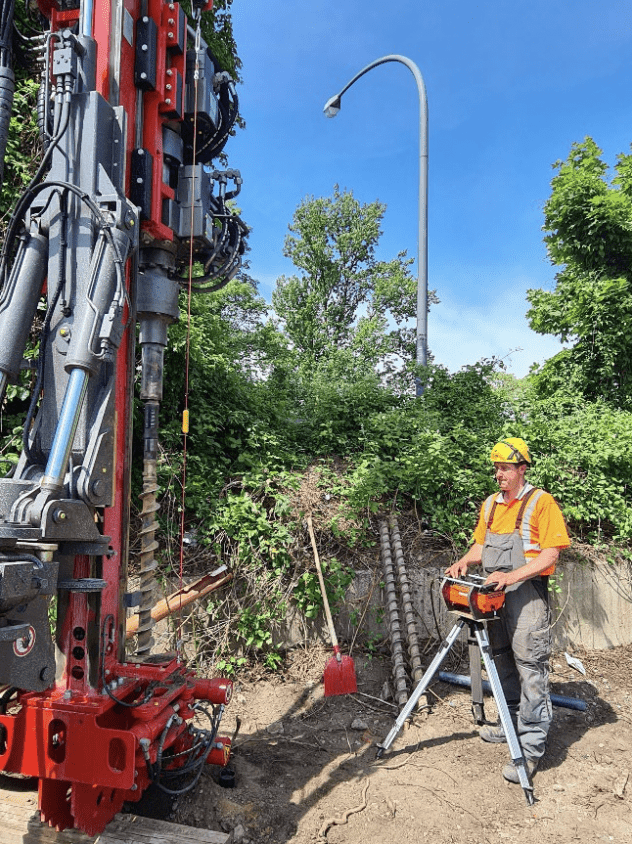

This is also the case on a current construction site of company GbE Grundbau Essen GmbH near Essen’s main train station. Two office buildings and a parking garage will soon be built on the approximately one-hectare site in Hachestraße, where the railroad freight terminal was previously located. Here, the latest generation of a KLEMM KR 801-3GS drill rig is used to drill 27 boreholes in a specified grid down to eight metres below ground level – the ground level at the end of the war in 1945. The boreholes are drilled using the auger drilling method without flushing. This is because percussive drilling methods with hydraulic drifters or DTH hammers are generally not permissible due to the risk of explosion caused by vibrations from any unexploded ordnance that may be present. The boreholes have a diameter of 120 millimetres, into which a PVC pipe is installed after completion to stabilize the borehole for subsequent travel with the ferromagnetic probe.

“As a drilling operator, you have to have a lot of experience here in order to correctly interpret the invisible processes in the borehole – just on the basis of the rotation and feed behaviour, as well as the resulting noises during drilling,” said Timo Hölscher, the drilling operator in charge at GbE Grundbau Essen GmbH. “Of course, no one wants to risk drilling into an unexploded ordnance and thus causing it to explode, but a certain residual risk can never be completely ruled out. The precise and sensitive control of the KR 801-3GS already makes my work considerably easier, and the wireless remote control means that I’m not usually standing right next to the borehole.”

Once all the boreholes have been completed, the measurement is carried out by lowering the measuring probe (e.g. a vertical gradiometer) into the plastic pipe. Specialists later evaluated the measurement data obtained in this way on the computer. Then, depending on the results, either the ground is released or further measurements are taken.

If there are indications of old mining activities, exploratory drilling is carried out immediately if contamination with explosive ordnance can be ruled out. In this case, boreholes are also drilled in a defined grid using a flushing drilling method. Contrary to explosive ordnance exploration, this can also be carried out using the percussive drilling method if the subsurface requires it. Hits, or tapped cavities, are recognized by drilling specialists, either by the sagging of drill string or by the drying mud flow. The cavities’ size, location and course are then determined and mapped by further drilling in the vicinity of a hit. If necessary, a plastic pipe is inserted into these boreholes, through which the cavity is backfilled with cementitious building materials after the drilling work is completed.

Additional injection boreholes may be drilled to inject grout for further stabilization of the foundation soil via sleeve pipes.

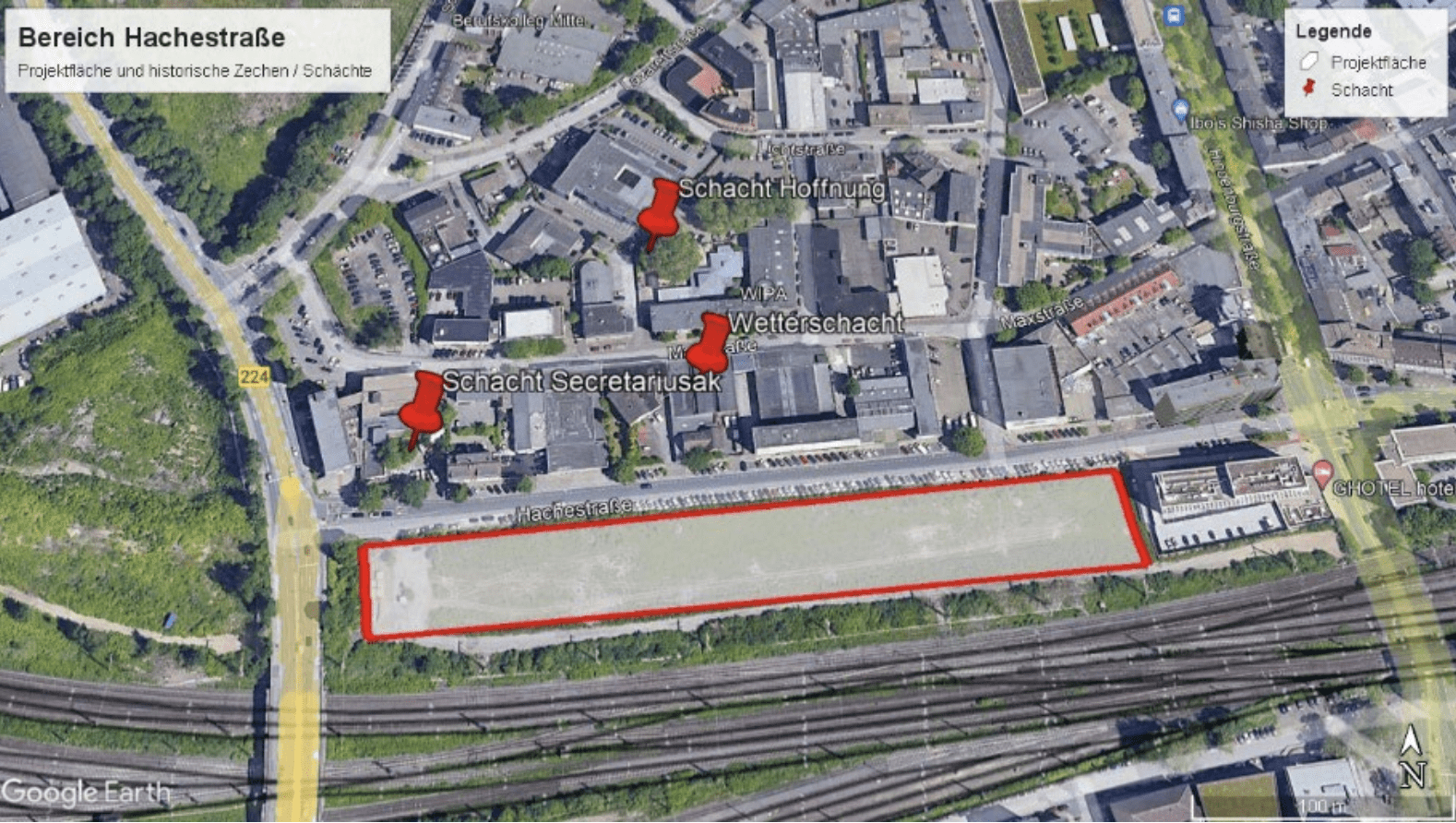

The construction site on Hachestraße is located in the direct neighbourhood of the shafts of three historic underground coal mines:

- Mine Secretarius Aak, mining from approximately 1750 to 1805, is 50 metres away.

- Mine Vereinigte Hoffnung und Sect. Aak shaft Hoffnung, mining activities from 1805 to 1897, is also 150 metres away.

- Mine Vereinigte Hoffnung und Sect. Aak ventilation shaft in seam Röttgersbank is 40 metres away.

During construction works on Hachestraße in 2013, cavities were discovered that can be assigned to the former mine field of the Vereinigte Hoffnung und Sect. Aak. After exploratory drilling, extensive backfilling work was deemed necessary. Therefore, test drillings will be carried out at the current construction site as soon as the exploration for explosive ordnance has been completed.

The KR 801-3GS defines its own class of compact and, at the same time, universally applicable drill rigs. Mounted on oscillating tracks, the drill rig is ideal for almost all jobs encountered in special civil engineering – from light to heavy drilling works. Equipped as standard with KLEMM Power Sharing, a power-optimized hydraulic system, KLEMM’s energy efficiency package, adaptive r.p.m. control of the engine and fan, and effective sound insulation hoods, the unit, with its low emission values is also ideally suited for inner-city use. The ergonomic design, easily maintainable, fail-safe machine controls with remote diagnostics, remote control operation and extensive safety features round off the package.

Despite the modern machines and processes available today, the search for, and removal of, relics of war and mining will remain a task for many generations to come on the Rhine and Ruhr.