It was more than half a century ago that soil mixing was first introduced in Japan as a method to help stabilize soils with low-bearing capacity. However, it’s only been fairly recently that the technique has become more commonly used in the Canadian construction industry.

Claude Berard, a senior project manager with Keller North America’s Edmonton office, says there are two primary reasons why soil mixing is becoming an increasingly popular option for many contractors in this country. First, Canadian contractors have become more efficient and are now better able to reduce the mobilization costs associated with using the technique. Second, he points out that an increasing number of U.S. firms have adopted soil mixing, which in turn has prompted Canadian companies to take a closer look at the technique.

“In Canada, things happen very slowly. Nobody wants to be the first in Canada. We always want to be third or fourth,” he said, laughing. “People are seeing it happening more in the States with project reports and there’s more of a level of comfort among engineers here now. They’re saying, ‘It’s being used everywhere else, we better get onboard as well.’”

Transforming marginal land

Brian Wilson, vice president of Keller’s Pacific region operations, concurs. He says recent innovations in soil mixing techniques and tools have helped it become more commonly adopted. The increasing demand in urban centres to transform marginal land into developable property is also spurring many consultants and contractors to take a closer look at how soil mixing could help.

“As cities continue to develop, the pressure to develop on that marginal land has increased and has driven innovation to find ways of improving the soil in a cost-effective method,” Wilson said. “Traditionally, that has been to drive piles, but driving piles can have a high cost and it’s not always a panacea. With soil mixing, you can develop some of that more marginal land in a more cost-effective way.”

So, what exactly is soil mixing? In simple terms, it’s the in-situ blending of native soil with a dry, cementitious powder, or a slurry of cement and water, using an auger or specially designed mixing tool. The combined materials create a zone of improved soil, typically in the form of columns or panels, that exhibit enhanced engineering properties such as higher strength, reduced compressibility or lower permeability.

Soil mixing can be used for a wide range of applications, including: reducing potential settlements under sensitive structures like oil tanks, increasing the bearing capacity of weak soil, enhancing shear resistance, building hydraulic cut-offs, reducing active earth pressure behind vertical retaining structures and even mitigating liquefaction beneath structures.

There are several different types of soil mixing methods used in North America and each has its own particular strengths and advantages.

There are two basic forms of soil mixing: dry and wet. In dry mixing, dry cement is pumped directly into the soil to make a weak form of concrete that’s also known as “soilcrete.” It’s typically only used in areas where the soil has extremely high moisture content and is not that common in Canada. In wet mixing, a slurry of water and cement powder is injected through a hollow stem at the base of the mixing tool during drilling.

An attractive alternative

While soil mixing is never going to replace piling, it can be an attractive alternative in some situations where the soil is weak or where the contractor wants to reduce the amount of material excavated from below the surface.

There are several factors a contractor needs to consider to determine if soil mixing is the best method to apply on a project. Hubert Guimont, engineering and business development manager with Menard Canada’s Montreal office, says one of the key considerations when it comes to using soil mixing as a ground improvement technique is the type of soil in the area where the project is being built. If the ground is full of boulders or construction debris soil, there could be premature refusal and soil mixing might not be the best choice. Alternatively, if more conventional structural methods are too expensive or complicated to use on a project, that’s when an alternative method like soil mixing might be the best option, he says.

“In soil mixing it’s really driven by the soil,” Guimont said. “You need to compose based on what the ground gives you and you try to optimize it. For example, in well-graded sand and gravel, you will make a good natural concrete. On the other hand, if you have too much clay or fine content, you might not achieve the UCS (Unconfined Compressive Strength) resistance on your final soil mix concrete.”

The size of the job is another important determinant in whether soil mixing is the right choice for a project, says Berard. Typically, soil mixing mobilization costs range between $100,000 and $200,000 compared to as little as $50,000 for piling mobilization. Berard says that means on smaller commercial projects, such as a gas station or grocery store, soil mixing can be cost prohibitive. He adds that’s why soil mixing is more commonly used on large scale projects where there is soft soil and needs reinforcement for heavier loads such as oil tanks.

“If the area is too small it’s just not economical,” he said.

Reaching greater depths

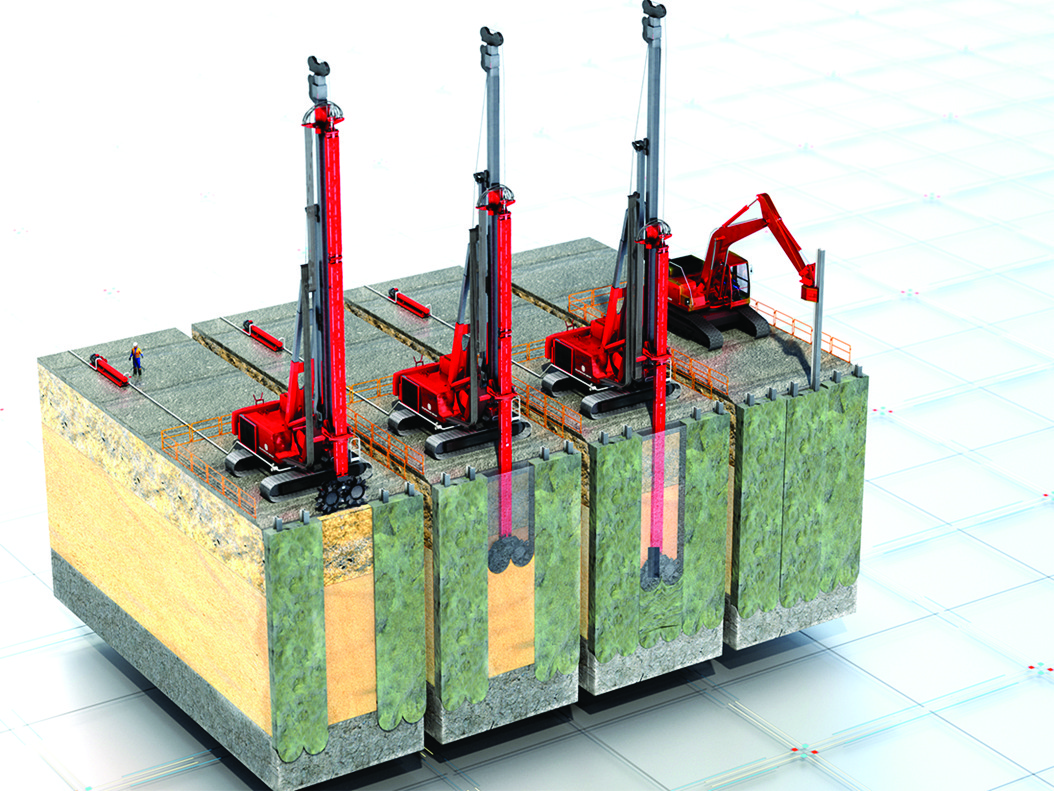

There are several different types of soil mixing methods used in North America and each has its own particular strengths and advantages. One of the increasingly popular methods is known as cutter soil mixing (CSM), which can be used in nearly any type of soil. In this method, cutter wheels rotate on horizontal axes mounted on the end of a Kelly bar and cut into the soil to form a rectangular panel of soil. A cement slurry is pumped through a nozzle located between the wheels and mixed with the in-situ soils in that panel.

Wilson says one of the advantages of the CSM method is that it can be used to reach greater depths than with other soil mixing methods. Typical panel depths are between 25 and 35 metres, although depths of up to 50 metres are possible with larger base carriers. The CSM method is commonly used to build temporary shoring walls for basement excavations and underground parking lots. As individual panels are as long as 2.8 metres, fewer joints are required when compared to a conventional secant pile or single axis soil mix wall, and the potential for seepage can be reduced.

In dry mixing, dry cement is pumped directly into the soil to make a weak form of concrete that’s also known as “soilcrete.”

“The soil conditions in parts of B.C. tend to lend themselves to it,” Wilson said of the CSM method. “The growth of it has largely been because we’ve got the experience and because people have been exposed to it, so it has sort of grown organically here. Once it starts to get established in other areas, I think it will pick up there too – in the right soil conditions.”

Another advantage of the CSM method and other soil mixing techniques is that they require far less spoil to be extracted from the ground than other, more traditional drilling techniques, and can reduce the carbon footprint of a project. Berard estimates that CSM produces 30 or 40 per cent of the amount of extracted soil that piling does, making far less impact on the ground and in most cases is a cheaper alternative since far less extracted material has to be hauled away to another site.

Another popular option when it comes to deep soil mixing (i.e. six metres or deeper) is the use of an auger mixing tool that rotates on a vertical axis. Up to three augers can be attached to the end of a metal shaft that is drilled into the ground and directly injects a binding agent into the mixing zone. The advantage it has over cutter wheels, Guimont says, is that it’s a little more versatile and is less easily blocked by large rocks because of the spacing between the augers. It’s ideal for producing a cheaper alternative to secant pile walls.

Popular option for pipelines and aqueducts

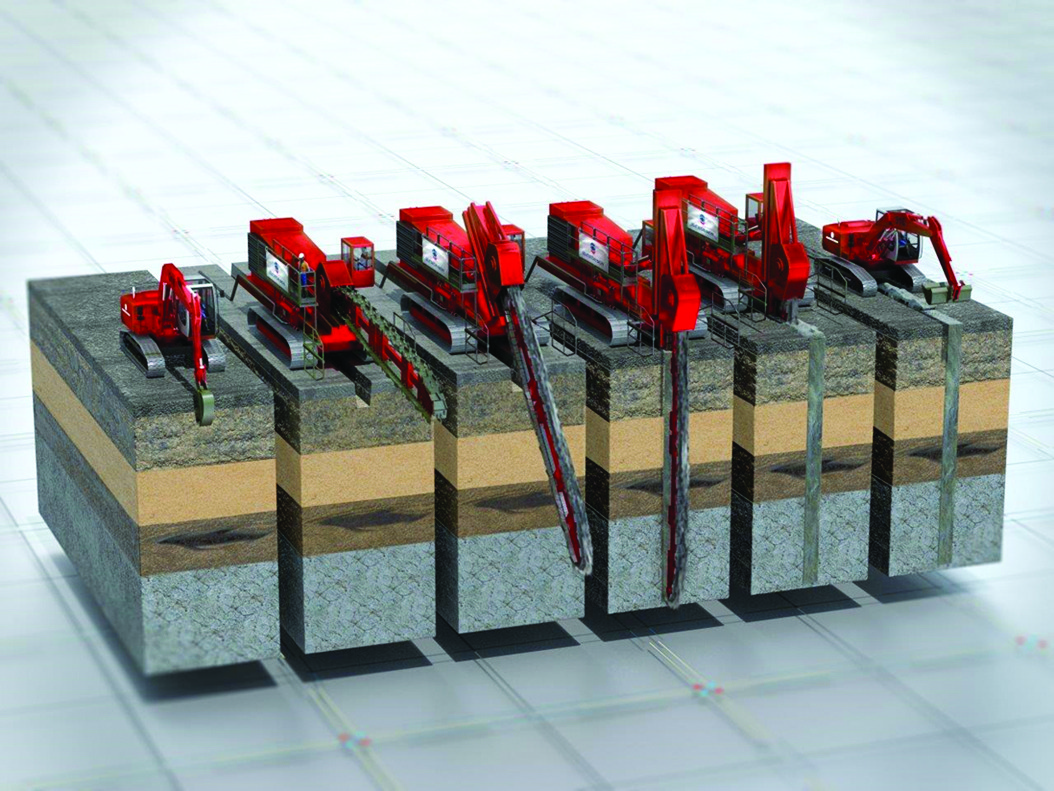

When it comes to long, linear projects such as the installation of pipelines and aqueducts, the Trenchmix technique of soil mixing is often the best option since it forms a continuous soil-mix wall, offers improved overall ground stability and also limits settling.

The Trenchmix tool is a 10- to 15-metre-long blade that looks like a giant chainsaw. It’s lowered into the ground where it then breaks up the soil and mixes it with a wet or dry binding agent while the blade is pulled horizontally through the soil. Although it’s not suitable for use in projects that cover short distances or require complex patterns, Guimont says the device is ideal “where you have continuous linear projects with hundreds of linear metres.”

Increasing frequency

Berard is confident soil mixing will be used by more and more Canadian contractors as they learn what it has to offer, and as the tools and techniques that are used continue to improve.

“Our experience level is way higher now than it was 15 years ago when we were almost guessing and there were a lot of unknowns. The rigs and tooling are better, the instrumentation is better and our knowledge is better,” he said.