Audits, injury rates and rule enforcement are commonly used in industry to assess and manage safety performance and to identify areas for improvement. This is how safety is represented by insurance companies, auditing agencies and regulators. But while these traditional tools can provide some insight into the current state of safety within an organization, they are not sufficient on their own to ensure the ongoing prevention of serious injuries and fatalities.

Organizations generally believe that they are safe because they keep their injury rate low.

Reducing injury rates is important. But a lack of low-risk injuries does not mean that critical risks are well managed. And new evidence from the Construction Safety Research Alliance at the University of Colorado has shown that many of the injury frequency metrics diligently tracked and monitored by organizations are statistically invalid and should not be used to compare safety performance between companies or businesses.

Organizations generally believe that they are safe because they pass external safety management system audits.

Having an audited safety program is important. But documents are not proof of the effectiveness of the processes that were documented.

Safety is not in discipline. Workers are not a problem to be controlled – in fact, they have the valuable information we need to ensure risk is managed effectively.

That statement and other concerns are raised in a recent study of the construction sector from the Safety Science Innovation Lab at Griffith University, showing safety audits tend to focus primarily on documentation and not real risk.

Organizations generally believe that they are safe because they use discipline to address most incidents.

Ensuring compliance is important. But if these same people normally do good work and they were well intended, do they really deserve punishment?

Important work by the U.S. Department of Energy revealed that instead of 90 per cent of accidents being caused by human error as commonly thought, up to 70 per cent of those accidents stem from an underlying systemic cause, and discipline does nothing to address those underlying causes.

Good organizations should, of course, continue to monitor their injury rates and reduce compensation premiums, and they should continue audit their safety management systems to receive the benefits of being COR certified. And they have the right to administer progressive discipline for safety violations.

However, plateaued injury rates and audit scores and a reliance on fault-finding may be an indicator that current practices and principles have reached their limit of effectiveness, and that a different approach is required to see an improvement in safety.

What is the goal?

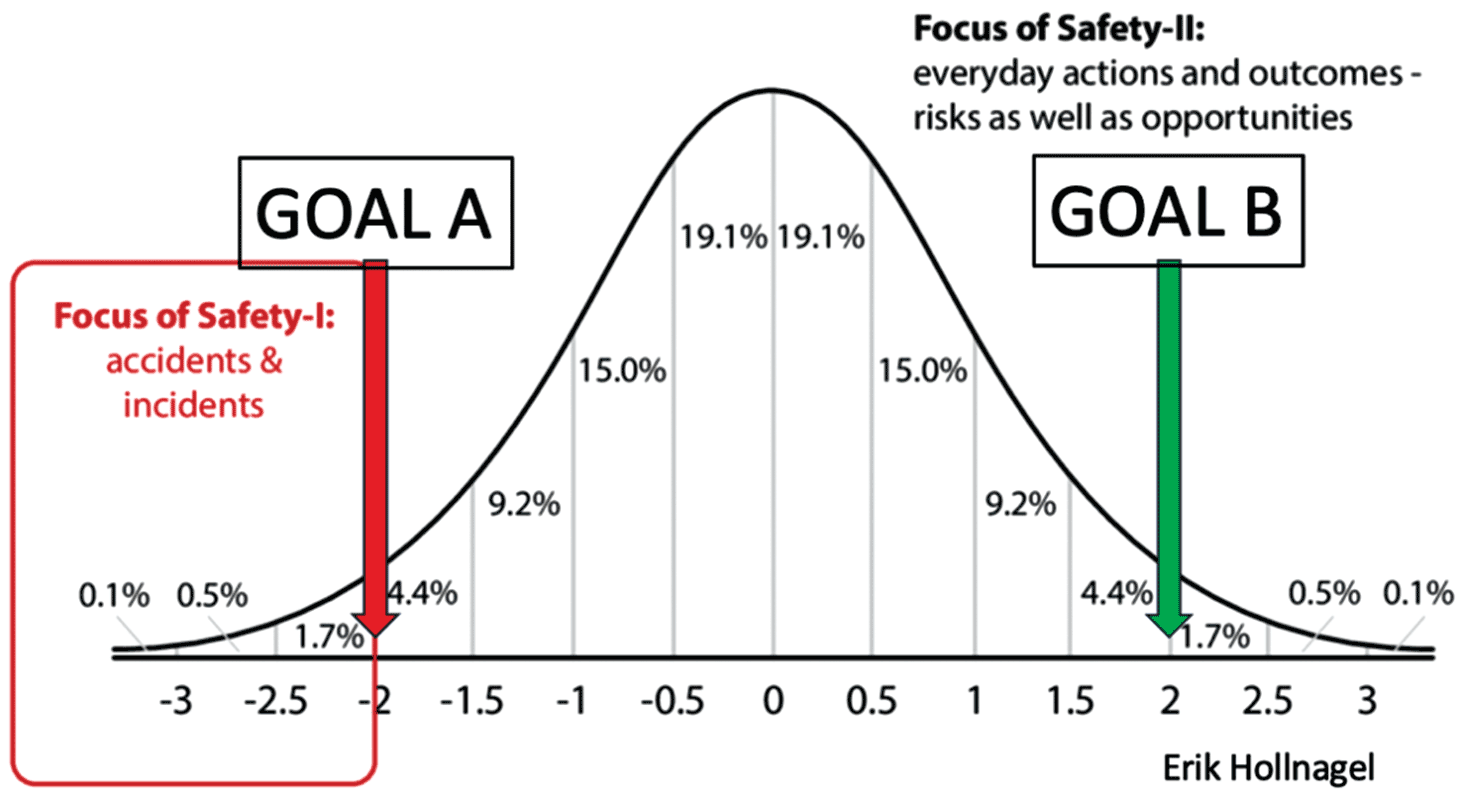

If all operational outcomes were plotted on a curve, it might look like the below, with the worst days on the far left, the best days on the far right and most “normal” days in the middle.

Safety has historically (and logically) been about preventing unwanted outcomes or ensuring as little as possible goes wrong. The “goal” has been to hold the line at Goal A, and is usually expressed as “everyone goes home with their fingers and toes” or “as good as they came to work.” The focus has been on accidents and incidents, and that mindset that has helped industry to become as safe as it is today. Call that the Safety-I mindset.

However, going home as well as you came to work isn’t a very good “goal” – it’s the minimum standard.

The new Safety-II mindset, while still encompassing the things currently done in Safety-I, also focuses on creating the desired operational outcomes, or “ensuring as much as possible goes well,” shown below as Goal B. This allows organizations to look at the majority of “normal work” through a different lens that captures performance potential, not merely deficit.

An analogy for this change from “compliance and conformance” to “operational performance excellence” can be found by looking at professional sports.

Safety regulators are like a sports league, creating rules and regulations, governing the conduct of players and teams and using referees to apply and enforce the rules to keep the game fair and safe. Organizations are like sports teams, comprised of owners, management, coaches and players, who all strive to achieve common goals in the field while avoiding costly penalties and devastating injuries.

This is all important and necessary because no team (or organization) wants their players (or workers) injured, nor do they want to be penalized, and they do not set out to violate the rules of the game. However, the rules of the sport should not be confused with how to play excellent sport.

For nearly a century, employers have relied heavily on meeting regulatory standards and in recent years they have established management systems to sustain that effort. But now the knowledge exists to make those systems perform like never before.

While regulators and auditors provide an essential function by prescribing what must be done and by judging and penalizing non-compliance, they are not experts in knowing what organizations need to do in order to reliably achieve productivity, safety and quality in their operations, something professor Erik Hollnagel, Ph.D., calls “synesis”.

And in sports, there are examples where in the pursuit of excellence, teams and athletes proactively innovated and improved their performance:

- In the 1930s, Candy Cummings invented the curveball in baseball, causing a stir among batters and prompting the pitch to be temporarily banned due to its effectiveness.

- In the 1960s, Dick Fosbury revolutionized the way the high jump was performed by perfecting a method that came to be known as the “Fosbury Flop,” the dominant style in the sport to this day.

- In the 1980s, Wayne Gretzky and his Oilers teammates’ proficiency in exploiting open ice led to the NHL temporarily eliminating four-on-fours, known as the “Gretzky Rule.”

These advancements weren’t made by focusing on the rules themselves as the goal, (Goal A); they were made by looking beyond compliance at all that is necessary for performance (Goal B).

Unlike the leagues in two of these examples, safety regulators and auditing authorities will not prohibit organizations from adopting principles from contemporary safety science, or from applying current best practices.

However, they also do not actively promote these advancements, as the onus lies on organizations to first realize the need and then take initiative in improving safety beyond minimum regulatory requirements.

Going home as well as you came to work isn’t a very good “goal” – it’s the minimum standard.

Created by Dr. Todd Conklin from Los Alamos National Laboratory, Human and Organizational Performance (HOP) is helping organizations both large and small to question “the way they’ve always done workplace safety,” and to move forward in more robust ways.

HOP is based on decades of research about safety culture and human performance in the nuclear sector that has been reinterpreted considering modern safety theories like Safety-II (Hollnagel) and Safety Differently (Dekker), making it applicable to all organizations.

Importantly, HOP is not another new program or initiative that must be rolled out on top of existing ones. HOP is a principle-based lens through which organizations can rethink and even redefine safety and what creates it. They can then look at their current practices and, with the valuable insights of those who perform the work, learn about the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in operational performance in ways they never could before.

Organizational culture

In 2002, the International Atomic Energy Agency explained that safety culture in organizations typically evolves from a “rule-based” phase (where the goal is to comply with imposed safety requirements) to a “system-based” phase (where the goal is to maintain an audited compliance-based safety management system). But to ensure reliable and resilient safety performance, organizations need to enter a “learning and improvement” phase that then informs the system as a whole and makes it perform better in modern times.

For nearly 20 years, Certificate of Recognition (COR)-based safety management programs have gained popularity in the industrial sector for their focus on continuous improvement and proactive risk management. But over that time, little has changed in how safety is thought about or how requirements like hazard identification and control, inspection and investigation are done.

The information is now available to help organizations evolve their safety systems. By learning how to proactively recognize the weak signals that hinder performance and contribute to accidents, companies can implement systemic changes to improve operational performance and prevent future incidents. This holistic approach to safety management ensures that improvements are sustainable and embedded within an organization’s culture.

By incorporating HOP principles into COR-based safety programs, organizations can elevate their safety practices to a new level. Decades of research has evolved into principles and practices that industrial organizations can now practically apply. Integration of HOP principles and Learning Teams into COR programs is a strategic investment in the long-term success and sustainability of industrial operations.

Remember:

- Safety is not in discipline. Workers are not a problem to be controlled – in fact, they have the valuable information we need to ensure risk is managed effectively.

- Safety is not in low injury rates. It’s in the ability to ensure critical controls are in place, and in the organizational capacity to perform work reliably well.

- Safety is not in documentation. Safety management systems (“safety work”) should support the safe execution of work (“the safety of work”), not the other way around.