People are always skeptical,” said Thomas Huckabee. “It’s been a very tough sell because it almost sounds too good to be true. People have known one way for the past 30 or 40 years. When you tell people there’s a way that’s safer, faster and costs less, they don’t really believe you.”

This is surprising because Huckabee seems anything but disingenuous. Huckabee is from south Louisiana and grew up around boat docks and oil docks, and always wanted to be involved with docks somehow. He studied naval architecture and is presently the operations manager at Pilecap Inc., a Texas-based firm that specializes in the cleaning, inspection and repair of marine piles. Pilecap started in the mid-1990s because “a lot of companies were spending a lot of money installing new piles,” said Huckabee. “We thought we could repair them instead.”

Concrete and steel piles in marine environments are prone to structural damage over time. In the case of concrete piles in tidal zones, also known as “splash zones,” water gets inside because concrete is porous. Once inside, the trapped water eventually evaporates. After a time, the constant ingress and egress of water causes sections of concrete to begin slowly chipping away.

In the case of steel, the material corrodes in marine environments with some settings being harsher than others. According to Huckabee, in Alaskan coastal waters “certain bacteria present in the water can accelerate the corrosion of steel piles as much as 400 times.”

When corrosion of steel or chipping of concrete is first observed, the next step is to determine just how bad the damage is. To do that, the piles first have to be thoroughly cleaned. “After piles have been in water for several years,” said Huckabee, “you get a lot of marine growth.” The accumulated growth first has to be stripped away to assess the extent of the damage to the submerged pile.

“Typically,” said Huckabee, “what happens is a diver goes down with a pressure washer, not unlike something you’d see at a carwash, and shoots several thousand psi [pounds per square inch] of water to clean a pile.” However, according to Huckabee, there are several drawbacks to the existing method. First, it’s an inefficient process. Dive teams can be slow, especially in water with poor visibility. There is also the possibility that portions of the pile will be missed and won’t be properly cleaned during the process. Second, there are significant safety concerns. “Anytime someone is submerged under water for an extended period,” said Huckabee, “that is a potential hazard.”

In most cases where the water is too murky or too deep, the dive teams are effectively operating blind. This also increases the likelihood of injury. An added potential cause of injury is the pressure washer itself. If the diver inadvertently sprays their self, the pressure required to clean marine piles is so high that the risk of bodily harm is considerable. This problem has been addressed by making spray nozzles longer to reduce the likelihood that divers might spray themselves. However, longer nozzles limit the diver’s ability to turn and manoeuvre, and this in turn creates a further hazard.

Third, using dive teams can be costly and labour-intensive. The work often involves long days with at least five-man teams and an average cost of $10,000 per day. “In order to save time, money and dramatically improve safety,” said Huckabee, “Pilecap started developing an automated pile cleaning system 15 years ago.”

Pilecap developed a ring-shaped system that clamps around a pile’s circumference. It can be set up around a pile by one person in as little as 10 to 15 minutes. Once set up, it dispenses 15,000 gallons of water per minute through five nozzles. The machine rotates clockwise and then counterclockwise back to its original position. “Nine out of 10 times the pile is cleaned with just one spin,” said Huckabee. It cleans one 18-inch section at a time and is then moved down the length of the pile using a track system. The tracks also have a built-in suspension system so the clamp ring can expand to pass over especially thick rings of marine growth.

Pilecap’s forthrightly named “Automated Pile Cleaning System” represents a significant improvement over existing diving-based methods. “This is basically five times as fast as you could get the job done with a dive cleaning time,” said Huckabee. The jets are kept six inches away from the pile itself. For cleaning steel, Pilecap uses 15,000 psi, which manages to clean a pile down to bare steel. For concrete, their team uses 8,000 to 10,000 psi. Pilecap also designed the system so it can be scaled up or down easily. “The smallest we’ve done,” said Huckabee, “is 12¾ inches and the largest was 57½ inches.”

After a pile is cleaned, the machine operator lets the water settle and then uses specialized underwater cameras to assess the pile. “Pilecap has a lot of expertise in inspecting piles, pipelines, docks, tanks, wharfs and pretty much anything under water,” said Huckabee. “The best part of this is that if we clean and inspect them, we can also repair them. We can usually do two to three pile jackets per day, up to 25-foot sections. The alternative is that the client will have to drive new piles,” said Huckabee.

Pilecap effectively offers “one-stop shopping.” For projects in which clients may have to hire three separate contractors for cleaning, inspection and repair, Pilecap offers all three services.

Though, it’s been a long process to get the Automated Pile Cleaning System to where it is today. “This is the fifth time we’ve been through it,” said Huckabee, “and it has definitely changed a lot over the years.” The initial iterations used hydraulics, but proved to be maintenance intensive. Pneumatic motors were used as well, but those required a dedicated operator.

Earlier machines required a lot of manpower. “Originally, we’d need a crew of four or five people: two guys taking it off and putting it on, one guy running air for the pneumatic motor, one guy watching and one on the controls,” said Huckabee. By constantly refining the process, Pilecap has now pared it down to just one operator, and the cost savings to the end user are considerable. “We’re presently on our fifth iteration and it is controlled entirely above water from a laptop. The fact that we don’t put anyone in the water is a huge, huge safety factor and is definitely our biggest selling point.”

Ease of repair is a further benefit of the current iteration. Huckabee said, “We’ve also purposefully designed it so that it can be repaired on site in case of damage. This was done to reduce downtime. We designed the system so that even a relatively inexperienced operator should be able to go to a nearby hardware store and get the machine up and running. We learned through experience that it’s best to keep custom parts to a minimum.”

Still, in spite of the many advantages of Pilecap’s cleaning machine, getting business has been challenging. Certain clients like oil companies or companies operating in corrosion prone Alaskan waters may require yearly inspections and repairs. For the most part though, pile inspection, cleaning and repair are the last things on people’s minds. It’s one of those “out of sight, out of mind” sort of situations and clients don’t usually approach Huckabee until they are faced with imminent structural failure.

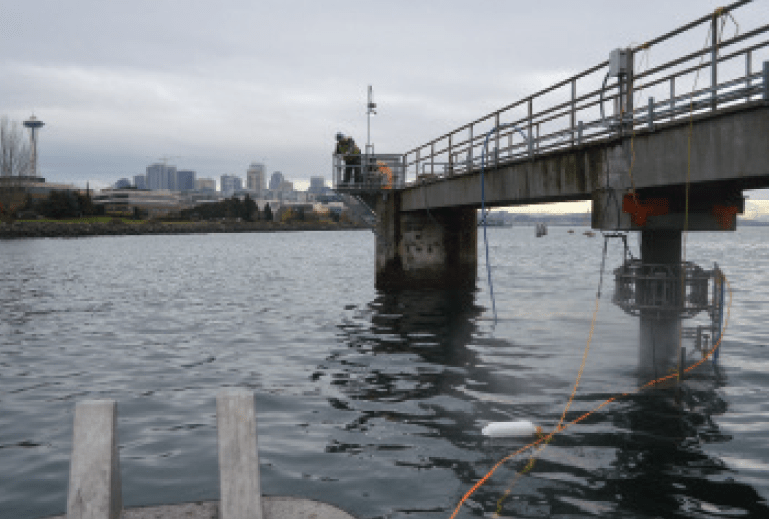

It can also be easier to find work when a pier is highly visible to the public. A project Pilecap recently completed was Seattle’s Pier 86 in Washington state. “The pier there, the public can see it,” said Huckabee. “Anytime the public can go on the pier and see visible damage, people get a little more worried and authorities are more open to a decent maintenance schedule.” The Seattle project is clearly a feather in the Pilecap team’s cap. “We cleaned 36 piles, jacketed two of them and saved them quite a bit of money.”

Despite the challenges, Pilecap seems to be poised for some major growth. Pilecap will be scaling operations by renting out their machines to end users. They can provide the necessary training to an operator in as little as five days.

They are also in the process of formalizing an arrangement with a Turkish distributor that will handle Russia, the Middle East, and Africa. While “every part of the system is patented,” Huckabee says they do worry if international laws will be respected, and what sorts of recourse will be available to them if someone decides to reverse engineer their technology.

“We’re working with a huge team of lawyers, but it’ll still keep you up at night,” said Huckabee. On the other hand, the firm Pilecap has licensed to use and distribute their pile cleaning technology is currently bidding on six separate projects around the world that collectively represent thousands of pilings.